Why is everything melting? 🫠

A doctrine of signatures for the end times (and an examination of the liquefying aesthetics of gen-Z) from Anna Sigrithur

Today we’re turning over the blog to Anna Sigrithur (Waxing Gibbous) for an exploration of the signature “melting” aesthetics of gen-Z art and, like, what it means maaan. We’re extremely pleased to present the piece, and to introduce Anna, whose blog we couldn’t recommend more highly for occasional dispatches on food, misguided bylaws, the distinct smell of Canadian Tire, and more.

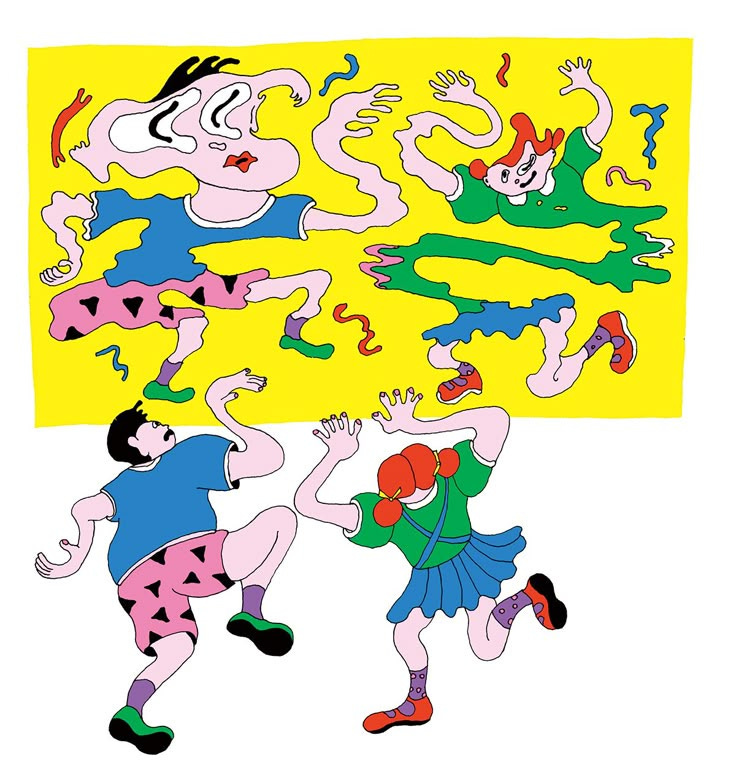

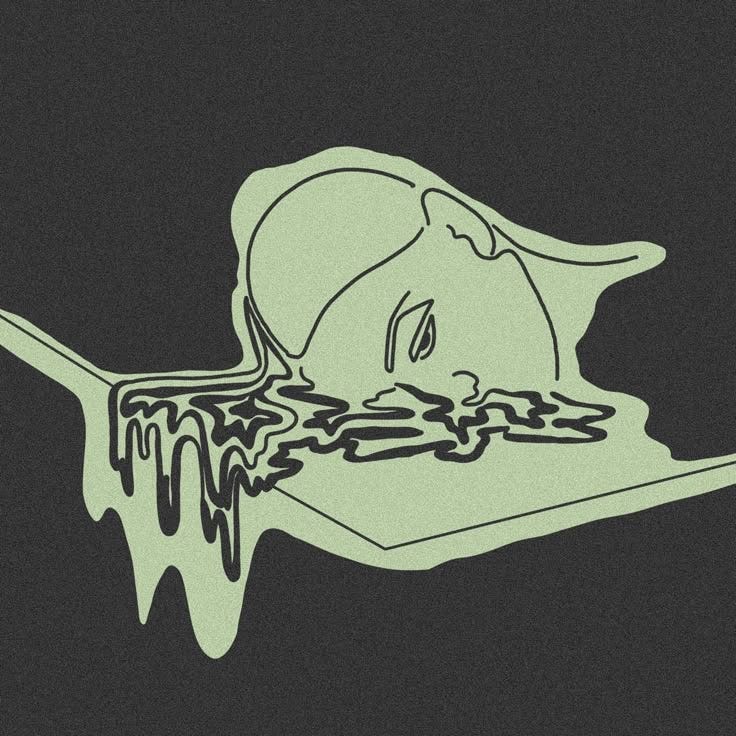

Maybe you, like me, took one look at the above image and immediately felt a pang of recognition. It’s a style of graphic illustration that’s trendy these days: characterized by a vaguely surrealist ugliness, in which wobbly, squiggly, melting and contorted shapes dominate, yet are often framed by some geometric element that offsets the wonkiness; in this case, a satisfyingly square frame.

The gestalt is retro, psychedelic and even punk in the sense that it’s bad but intentionally so— but is it punk when the places I have seen it used the most is as product branding, like on $28 bags of coffee at bougie third wave coffee shops? It seems rather ironic; maybe that’s the point. Either way, once I started noticing this wobbly, melting aesthetic, it was suddenly everywhere— or, everywhere young and digital: in the branding for cafes, on indie bands’ Spotify profiles, in Instagram ads selling me trendy junk, inked on the arms of the stylish, and printed on garments. It didn’t stop there. A younger friend replied to a text message with an ambivalent “🫠” and I realized that emojis had caught the melt, too!

What to make of this predominance in melting representations in online culture and commercial branding alike? Much sleuthing over the past few weeks have yielded no clear or distinct answers. Does this trend even have a name? Surprisingly, given that we live in a world of increasingly niche online micro-trends1, I found fewer answers still. And so, while I still have not yet landed on totally solid ground, I do invite you to join me in enjoying what I have discovered these past two weeks as I’ve dug around through the muck and the melt.

Rotting in the ironic distance

While chatting about last week’s Gibbous and the season finale of Nathan Fielder’s The Rehearsal, my coworker J mentioned how he notices that it’s his friends in their 30s who appreciate Fielder’s brand of ironic humour the most— millennials2, in other words. Like me, Fielder is a millennial— albeit an elder millennial, born in 1983— and so this could indeed be the reason for my affinity with his humour. But do different generations have different senses of humour or irony?

While irony has been around since cavemen first bonked each other on the head and said ‘just kidding!’, many cultural commentators point to the internet as an accelerator of its formal evolution. One possible reason for this, writes critic Nathaniel Sloan is the distance the internet creates between us and our image:

“The ever-increasing mediation of our lived experience by social media means increasingly that we no longer do anything without considering how we might be perceived… This compulsive self-awareness correlates with an increase of ironic distance, leading to the blurring of the boundary between irony and sincerity.”

We are watching ourselves like never before: not just in the immediacy of a single mirror or lens, but in the compound-eyeball-like hall of mirrors that is social media. It’s as though we have now come to experience ourselves as viewable objects first, and real people second. Or, both at once, which is perhaps even more confusing. Regardless, as our self-view splits into pieces, it becomes increasingly harder to tell if we’re doing something sincerely, or for how it will appear. Netizens have taxonomized such ironic distance into categories of “post-” and “meta-” irony, terms that describe different structures of signification and meaning.

Here is a quick ‘101’ on those two terms for those, like me, who need it:

Regular irony is, in the broadest sense, a juxtaposition of what something appears to be, and what actually is or is expected. Examples include a fire station burning down, or saying “Isn’t this lovely weather,” when it’s crappy outside (the latter being a form also known as sarcasm).3 Meanwhile, post-irony, made (in)famous by millennials, subverts irony’s expectations one step further by circling back towards self-aware or put-on sincerity, the kind that begat the now infamous “i can haz cheezburger” type of cringey millennial meme.4

And now, one step beyond post-irony’s sincerity is meta-irony— often attributed to gen-Z— which is “purposefully awkward”, “unsettling” and confusing. It is, put most simply, an ironic use of irony,5 which is extremely difficult to untangle, seemingly even for gen-Z themselves.

Charlotte Legrand writes that, for a codex of meta irony, one only needs understand gen-Z’s use of emojis. She cites as an example the crying laughing face that signifies “sarcastic gloating, mocking the humour of those who would use the emoji ‘unironically’”. However, I would argue that this is still in the domain of post-irony (just an uncharitable application of it) and that the true Rosetta Stone in our emoji codex of meta-irony is, in fact, the melting face.

First introduced in 2019, the melting face emoji (🫠) quickly picked up traction during the pandemic, and grew quickly in popularity, peaking in 2022 when GQ declared that it was the emoji of the pandemic: it was “everywhere and all of us”.

So why is the melting face emoji meta-ironic? Well, unlike post-irony, in which doing something “ironically” is easy enough to trace backward the two steps of displacement to achieve the intended meaning, meta-irony has three steps. And with each step displaced from (but still referring to) sincerity, signifier and signified are complicated not linearly but rather exponentially as meanings begin to bounce around and diffract as though in that hall of mirrors.

Represented numerically, simple irony could look something like 1:1 = 2¹= 2, with 2 being the final layers of meaning. Post-irony then would be 1:(1:1) = 2² = 4 layers. Meta-irony last of all would be something like 1:(1:(1:1)) = 2³= 8 layers— simply too many to hold in the mind at once. No wonder its effects are “unsettling”!

While this math might seem a bit silly, it serves my point which is to say that with each layer of added complexity, at a certain point the coherence of the system degrades, resulting in the loss of fidelity: the semantic version of a photocopy of a photocopy. As philosopher Michel Serres would write of such phenomena, the noise takes over the signal. But as has been the case for art since the dawn of the age of mechanical reproduction, the noise always becomes another medium of cultural expression. And so, one theory for the melt is to class it alongside other internet-age recuperations of noise, such as ‘glitch art’ and ‘meme decay’: just the latest in the artistic embracing of unwanted technological artefacts.

Except, perhaps the technological artefact in this case is less visual so much as semantic: our symbolic system of language, refined over hundreds of thousands of years, jams and overheats with too much meaning and begins to melt. And I can’t help but nervously wonder “in millennial” what the implications of this are to be.

Anyway, meltingness can be seen in this light as a kind of doctrine of signatures for the post-modern loss of coherence reflected not just in and through the meta-irony of the internet, but in the reality of modern day life. Culture journalist Olivia Ovenden proposes that the melting face helps express a range of indeterminate feelings ranging from minor daily annoyances to climate despair. The somewhat flat affect produced by the emoji is understandable if read as overwhelm— a fair response to this unprecedented stack of looming and present catastrophes. Ovenden concludes, with a hallmark gen-Z deadpan, that the symbol is appropriate, given “[t]he planet is quite literally melting.” So, a visual representation of overwhelm as a generation deals with the bleakness of a certainly uncertain future: that is a second theory we might venture as to the doctrine of melty signatures.

A corollary to this theory is that gen-Z is known for being overall very fluid— most notably in the realm of gender identity, but in other ways, too. In a Guardian style article, the youthful consultants charged with making over a millennial editor credit their signature style with “the tendency to ‘think fluidly about everything’: not just about gender, but about work and social media.” (Ah, gender, work and social media: the three pillars of life.) Like the melting face emoji’s purported capacity for emotional range, fluidity also carries over to gen-Z’s social outlook that is an ironic combination of both “bleakness and optimism”. They’re the first generation to grow up amidst the certainty of planetary crisis; no wonder they’re trying to grapple with it by holding onto everything at once.

It bears mentioning that warping and melting have featured at other points in history as artistic or visual motifs, though most notably employed by the psychedelic and the surrealist art movements. Both these movements arose out of times of cultural upheaval, to which they responded with the iconoclastic impulse to explore of the nature of perceived reality itself, whether through altered states of psychedelic consciousness, or the surrealist’s preoccupation with the subconscious self and dreams. Dalí, a surrealist, was quoted as saying his ambition in painting was “to systematize confusion and thus to help discredit completely the world of reality.” There’s something about portraying the melting, or in Dalí’s case decaying— either way, deforming— of the otherwise solid world around us that produces the sense that our perceptions are not to be trusted.

However, I wonder if today’s predominance of melting is coming less from a singular artistic vision like that of Dalí, and is rather more emergent: a visual expression of the chronically-online existence in which each of us has, according to the interlocutors of the Guardian article, “multiple versions of yourself, rather than one linear, polished version.” Unlike Dalí who could stand back and play with perception unfaithfully, as more and more of our lives unfold digitally, we might be trapped in a low-fidelity hall of mirrors in which the nature of reality itself is melting from the real to its representation. In this case, fluidity is an adaptive strategy!

Social hieroglyphs

Just like both the melting face emoji and the Dalí piece shows, art and style will always respond to the social and economic contexts that surround us. And this brings me to another clue in the mystery of what at this point we might as well call the ‘Meta-Ironic Melt’.

Last year, a viral video by millennial YouTuber Nick Lewis pithily summarized the differences between millennial and gen-Z “aesthetics” — a phrasing that is, in and of itself, a something of a gen-Z innovation. What Lewis explains is that millennial design was rather geometric, favouring clean, mid century minimalist decor, chevron-patterned fabrics, and hexagon-shaped housewares. Contrast this to gen-Z’s style, which is much more post-modern and organic: featuring blob-shaped housewares, textiles festooned with wobbly checkerboards, weird and offbeat furniture, and yes, everything is warped and melting. Taken in this light, could the Melt simply be explained as a byproduct of gen-Z’s attempts at differentiation from millennials?

Cultural studies scholar Dick Hebdige, in his iconic 1979 text Subculture: The Meaning of Style, writes about the commercial and ideological forces that combine to create a style ‘dialectic’— the churning over in fashion as one new trend seeks to differentiate itself from the one immediately before it. In other words, the gen-Z wobbly checkerboard versus the millennial chevron. Hebdige writes:

“As soon as the original innovations which signify ‘subculture’ are translated into commodities and made generally available, they become ‘frozen’… Youth cultural styles may begin by issuing symbolic challenges, but they must inevitably end by establishing new sets of conventions.” (96)

In other words, he’s saying that it’s not just the subcultural originators of fashions that produce fashion’s fickleness, but the forces of commodification as well, as trendy youngsters seek to outrun the mainstreamification of their signature style. After all, are you still punk if everyone dresses like you? Thus both the subcultural denizens and the commercialists participate in “creating new commodities…or rejuvenating old ones” whether they like it or not.

Hebdige goes on to say (following Marx) that certain commodities are “social hieroglyphs”— objects that arrive to the market already laden with symbolic value that exceeds their use. In 1979 when Hebdige was writing, such fashions were largely recuperated from the people by companies— he uses patchwork rocker jackets as an example. In our 2025 world of hyper-branding, however, the creation now tends to go in both directions: companies themselves generate hieroglyphs in the forms of logos that we are supposed to wear like little walking billboards. And we do, we love it!

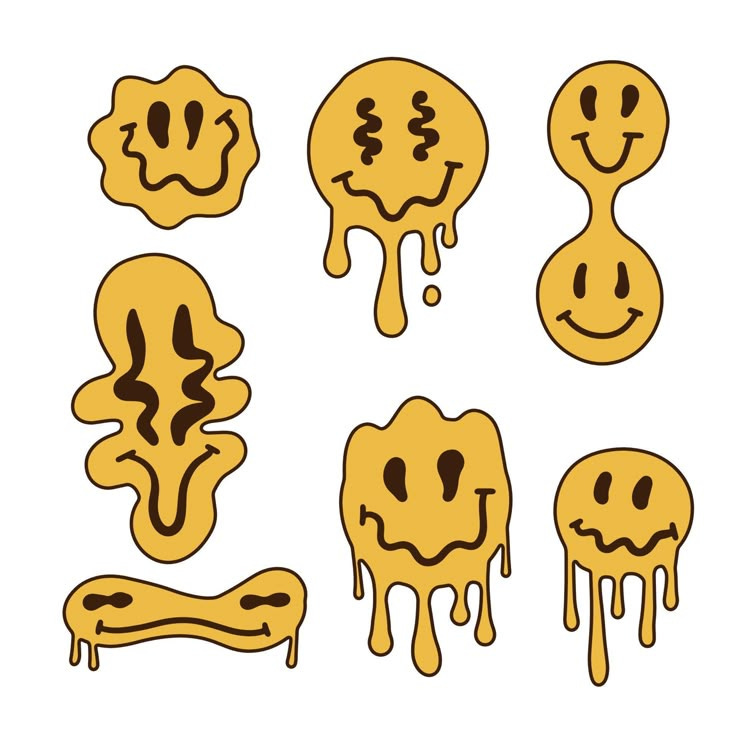

But one of the earliest of such commercially-generated hieroglyphs still endures: a symbol that features strongly both within today’s melty aesthetic and our codex of meta-irony: the smiley face.

Though its more primal origins are debated, the smiley face as we know it was a commodity from the start, created by American artist Harvey Ball who had been contracted by an insurance company to create a logo for an advertising campaign in 1963. The smiley took off into culture, and, over the last sixty-two years, it has been re-appropriated in various ways by subcultures from its original commercial context. Just think of Nirvana’s drunken-looking smiley logo with X’s for eyes that became a symbol of gen-X counterculture.

But the present symbolic value of the smiley face, in its now-ubiquitous melting representation is unclear. Does it mean anything, or is it now a symbol evacuated of meaning? Or, stranger still, a commodity evacuated of value? If anything, the contemporary usage of the smiley, much like the melting aesthetic, feels like just that: aesthetic— and not much else. Which is probably the point. Journalist Tatum Dooley’s description of the smiley face renaissance as “corporate grunge” therefore feels rather fitting: an oxymoron produced not by ignorance but by competing layers of self-reference that reduce meaning to incomprehensible static.

And so, the third and final theory about the melting aesthetic, and indeed the melting smiley face in particular, is less about the visual language and more about the embracing of commodification— as an economic practice and a symbolic practice— in a meta-ironic manner that amounts to nihilism. Novelist Karl Ove Knausgaard identifies contemporary nihilism as the flattening of the world through commodification. Such nihilism, he argues, is found at the root of seemingly common-sense liberal values of our time. He writes of nihilism:

“[T]he inclination to find a common denominator for all the complicated tendencies of the world… or the determination to convert everything to figures, beauty as well as forests as well as art as well as bodies. For what is money if not an entity that commodifies the most dissimilar things?”6

And so, on one hand, it feels like gen-Z is beating these flattening forces of commodification at their own game, with layers of meta-ironic meaning too inscrutable to decipher and fully recuperate. On the other hand, I suspect that many are cynically or nihilistically playing the game themselves. I don’t know; and that’s the thing: I don’t think any of us do anymore. I think everything’s gotten too blurred— too melted— to tell the difference.

Anna: “I write these essays for practice: the practice of noticing things and then the practice of articulating them. This almost always leads me to get lost as I realize I lack sufficient knowledge on the topic’s context to articulate it clearly— which I then try to remedy by reading and writing enough to find my way through the piece. Sometimes it is successful and I end up somewhere interesting. As many smart people have said, getting lost is important if you want to get somewhere new. Thank you to Discordia Review for sharing, and thank you for reading.”

This post originally ran June 4, 2025 on Waxing Gibbous. Visit Anna’s Substack now to subscribe.

Things are going to slide,

slide in all directions.

Won't be nothing,

nothing you can measure any more.

- Leonard Cohen

As I said, when I joined Substack in July (2025), I came to Substack, for intelligent discussion, and Anna, you are it! And wonderful to meet you at Spirit Garden too :D Peace & Light