Are YOU a NEGROPHOBE?

Darius James's bold hallucinogenic journey into race and racism in America

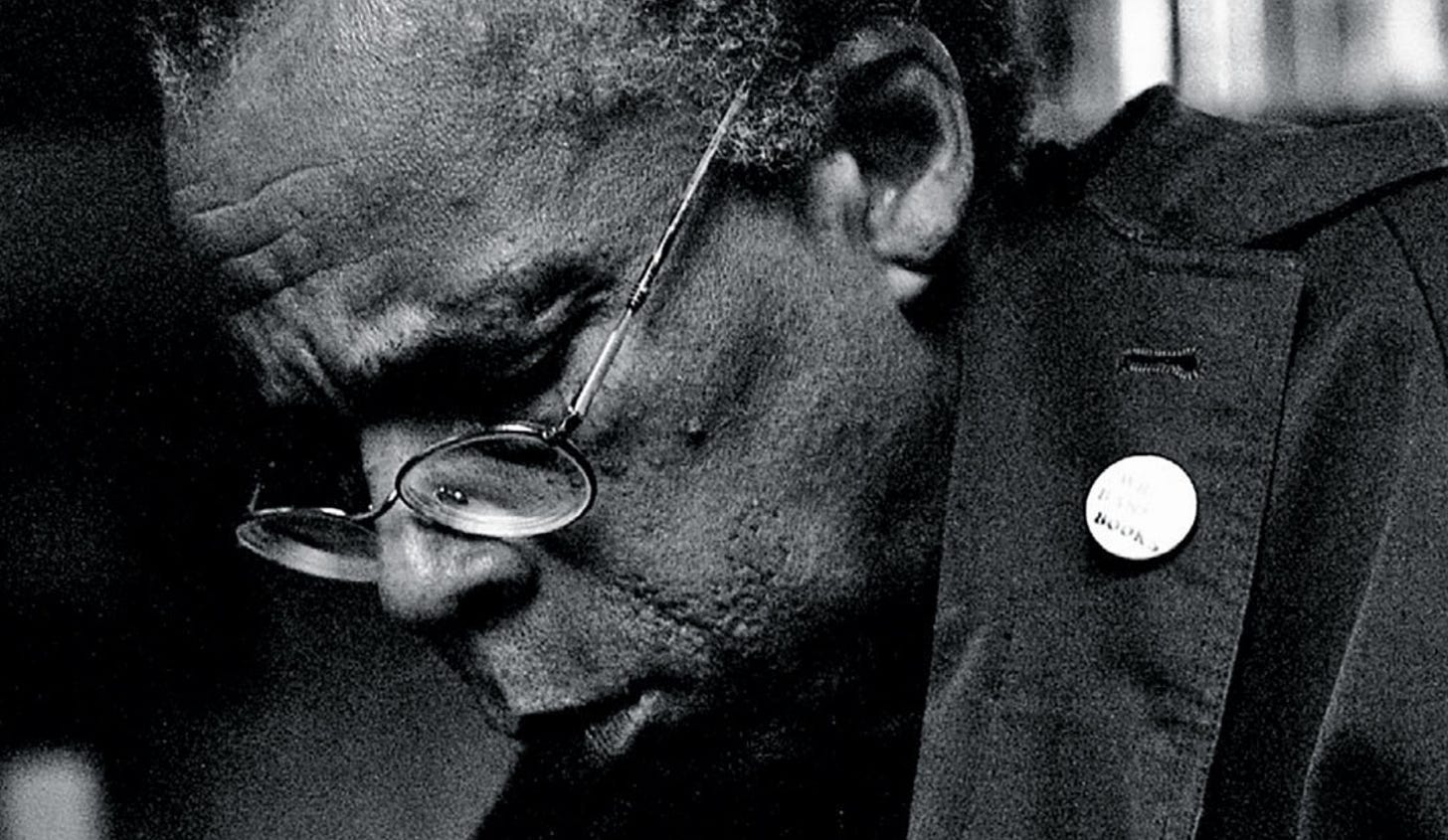

Darius James said he wanted to make people throw up, and he wasn’t fucking around.

James’s novel Negrophobia: An Urban Parable is a nauseating trip into “the dark,” here meaning both the unilluminated cultural psyche and one of its great preoccupations: the spectre of black people.1 Presented as a Blaxploitation/grindhouse matinee, Negrophobia isn’t about race in the more respectable, MFA-friendly sense of “identity” and “belonging” and fetishism of Christ-like “suffering” that redeems the consumer in the pacifying spectacle of “resilience.” What it’s about is race through the lens of racism as an obsessive and pornographic id kicking and screaming at the heart of our society, one that never goes to sleep and still reverberates through whatever infrastructure of liberal/neoliberal/post-racial whatever we plaster over it. It is intensely discomforting and the pages are so coated in congealed blood that they nearly stick to your fingers. Not since James Baldwin’s “Going to Meet the Man” has the psycho-sexual nature of racism been so uncomfortably and intimately prodded at, the parts of the cultural psyche that society least wants to confront, its darkest shadow. There is no “authenticity” to be nodded at—James gleefully tears categories like those apart. The haunted xerox of the ghetto that liberal bourgeois America can’t stop jerking off to in its condescending displays of “recognition” and “validation” is punctured and ripped straight through by every Jim Crow caricature and Br’er Rabbit grotesque come alive to strangle its makers. And yet it’s so funny. Horrifyingly, grotesquely funny. It can’t not be, because the twisted heart of racism, when exposed, is not just terrible and terrifying to look at, but also clownish.

James’s novel2 tells the story of Bubbles Brazil, a privileged white girl thrust into an Alice-in-Wonderland-like journey by a voodoo ritual and submerged in a world of caricature, of tar babies and minstrels, intercut with scenes of President Walt Disney presenting white supremacist Mickey Mouse, the rotting reanimated corpse of Malcolm X singing about pork, and a giant black robot created by a magical talking set of disembodied dreads—and, eventually, Bubbles herself is turned black. It is a novel on race that refuses to grovel for empathy nor provide its reader with a shot at redemption, instead wholly using its energies to skewer how American racism is inseparable from its obsession with visual spectacle and obscene fetish. James’s peers would include Kathy Acker (who loved the book and was an encouraging influence early on in its development), Ishmael Reed, GG Allin, William S. Burroughs, George Clinton, Sun Ra, and Ralph Bakshi—in fact I thought quite a bit about Bakshi’s Coonskin my first time around the novel.

I was particularly taken with the novel as an indigenous person, because there is so little I find in my own people’s work that displays this kind of confrontational truth, this ruthless and ugly vista—attempts to transgress beyond the boundaries of normative comfort usually just wind up falling into the trap of recognition fiction (I’m thinking of books like Joshua Whitehead’s Johnny Appleseed). But the hauntological aspects of colonialism, the indigenous future that never was, that warps and festers under the surface of “civilized” society, is far more twisted and grotesque than this literature ever dares to revel in, and it is immensely cathartic then to witness James produce something analogous from his own perspective. Much as Latin American fiction necessitated a move into “magical realism” as a literary mode more evocative of the overlaid dual-reality of “post”-colonial society than standard realism—and then taken up to the same effect by writers like Salman Rushdie in India, Rebeka Njau in Kenya, Eden Robinson in Canada, and so on—the somewhat neglected mode of “Afrosurrealism” does much to illuminate the darkly-psychedelic experiences arising from “double consciousness” and the palimpsest of racial history in America, and James utilizes this with aplomb. The shock that James delivers to the system through his psychedelic descent forces a true psychological confrontation about race and difference that one fights the impulse to turn away from, a Negrophobia-phobia, rather. The thing about a lot of “coloured fiction” these days is that it seldom feels “honest.” Many writers believe they pull no punches—but James is the real deal. James’s left-hook is a wallop.

His mastery should have made him a literary giant with acolytes and copycats. The sad thing is that James’s book came out all the way back in 1992 (I wasn’t even born yet). In a just world, this man would have become a literary titan, but we do not live in a just world, and so James’s planned follow-up novel never came to pass. His work was too misunderstood. James just doesn’t play into what publishers have conditioned us to expect of “racialized” fiction, which often focuses on the values we’ve already described above in pursuit, through “recognition,” of a kind of “uplift.” But the thing about uplift, as Grace Byron put it, is that “the desire to uplift instead of transform is, itself, conservative. Pushing at boundaries is always taboo.” There is further a belief by many that irony has no place in discussions of race, and that work about race should be the sole purview of the painfully serious,3 a position which has come to dominate racialized cultural production in recent years. There is a misplaced belief that this kind of solemnity is the sort of treatment a subject like racism—or really any serious topic—deserves. This is not merely a stifling position but a rather immature one as well. Expression is not literalism, ideas are conveyed in more than just the literal meanings of sentences (anyone who reads or writes literature should surely understand that), and there are truths about most subjects which cannot be conveyed without tools like irony and humour. There are things James is able to express that cannot be expressed otherwise, that cannot come across through simple explanation by way of direct language. What the man is playing with is something so deeply rooted in the subconscious that its peculiar leakage can only come squirting out by means of an aggressive cultural tickling.

You likely haven’t read this book, or possibly even heard of it, because evidently no soft-ass literati of the unbearably soft-ass literary landscape we’ve cultivated for ourselves has the balls to champion such a thing. It’s too raw, too confrontational, too weird, too uncomfortable, too outsider—that is to say it’s just too good for those sorts of people to possibly understand. But I am here to champion it. This is one of my all-time favourite novels. Buy this book. Buy it right the fuck now. It’s finally back in print through NYRB as of a few years ago. Click this link and spend that fifteen dollars and buy the thing. I’m going to wait for you to do that. Doot-doo-doo. I’m going to sing a song as I wait. Camptown ladies sing this song—

AND FOR ANOTHER DOSE OF A TRUE ORIGINAL, CHECK OUT OUR PIECE ON NORMAN SPINRAD:

I’ve gotten comments about my inconsistent capitalization a few times with regards to “black” (in some pieces I capitalize it, it some I don’t)—here I am choosing to use the lowercase because that is James’s choice in his book.

Which he told me, when I contacted him a little while ago to express my admiration, that he wrote here in my city of Montreal! He used to hang out at Foufs!

This point on irony is something I’m stealing from Michael A. Gonzales’s piece on Negrophobia, which he adapts from Greg Tate’s piece for Village Voice on Jay-Z’s music video for “The Story of OJ.” Gonzales’s piece helped inform my own and you can read his here. Coincidentally, Gonzales made a lot of the same artist comparisons that I had already made while first drafting this piece, which I suppose on one hand makes me feel more confident that my comparisons were well-made, but on the other hand makes my own piece feel redundant. Oh well! I highly recommend reading his piece as it is a lot more thorough and goes more in-depth into the history of James’s novel.

If Eris says so, then I'll fucking buy it because the writing is just so damn good and illuminating.

Doo da, doo da...