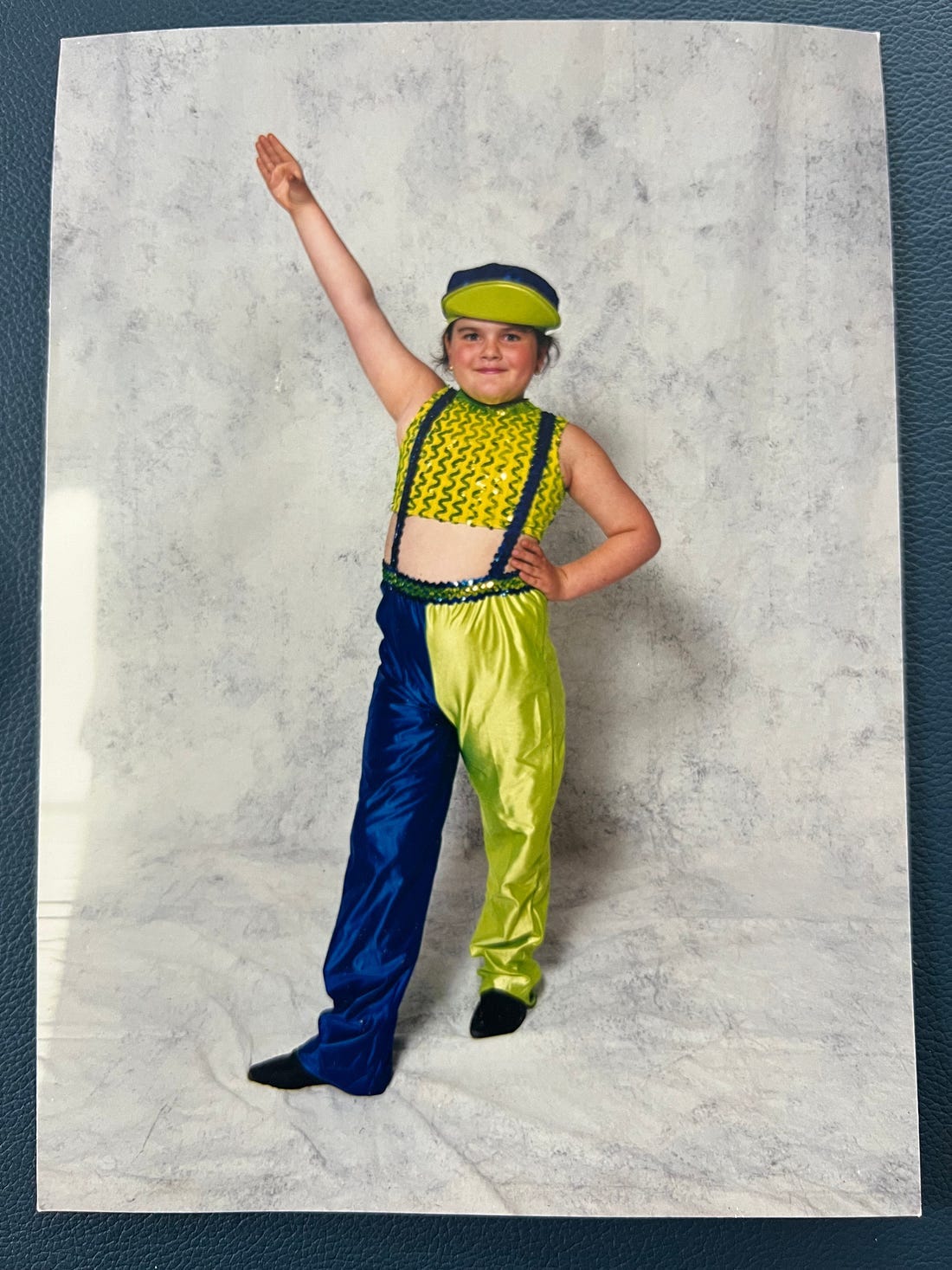

efferent and afferent humour

Tara McGowan-Ross's stab at a new philosophy of humour.

Today we’re turning over the blog to Theatre of Cruelty’s Tara McGowan Ross: Fellow Traveller, subject of a Wikipedia page, and general pal. We’ll let her introduce herself.

“Hi, I’m Tara, an urban Mi’kmaq writer with a philosophy degree I never shut up about. I wrote a memoir that was a finalist for the largest nonfiction award in Canada, which was a huge shocker to me personally because it was the first piece of prose I ever published. I also write fiction and poetry. The Discordia people bullied me into doing a post swap with them, so please enjoy this one.”

I hold humour in extremely high esteem. Sometimes I say mirth is my higher power.

My parents were both very funny. As a child, I quickly made it a high priority to make them laugh. I did more of what worked and less of what didn’t. I learned that humour was a way to act in the world: it could break the ice, comfort the sad, earn trust, and defuse tension. There are obvious ways of using humour in its expressive function: as a social strategy, a bonding mechanism, a method of taking what's inside you and putting it out.

But humour also works in the other direction. It can be a way of taking things in. When you look at something in order to notice what’s funny about it, you notice things you otherwise would not. I heard someone say recently that humour is the fastest way to signal intelligence—it was a dating coach, I think, saying that if you can make a girl laugh you can probably kiss her. But that’s still the expressive mode, the inside-out one. What I’m trying to say is that it’s also a way to look at the world. It’s a very effective mode of observing, of testing how things fit together, of engaging ideas with a playfulness that illuminates their logic and boundaries. I was trying to come up with a shorthand I could use to make this distinction, and I landed on efference and afference—terms from physiology that denote the way neurons carry information in the central nervous system: information moving from the brain to the body, or vice versa.1 Humour that acts on the world is efferent humour, humour that interprets the world is afferent. I believe this might be an original idea.

Humour as defensive strategy.

There is a way of thinking about humour that holds that it’s always born from pain. This is something that sounds very profound to just kind of throw out there in conversation. It’s not true.

When people say this, I think what they’re gesturing at is that humour can be used in a psychological function, as a defence mechanism. “Defence mechanism” sounds bad, like something you’re not supposed to do, but everyone uses defence mechanisms because everyone needs them. The more “immature” the defensive mechanism, the more negative impact it has on the person employing it—“primal” defensive mechanisms manifest in the symptoms of psychosis, and “immature” ones (slightly better, I guess) manifest in the symptoms of personality disorders.

Humour is one of the “mature” defence mechanisms: the most functional, perceived-virtuous type. Other mature defence mechanisms include suppression, which is when you make the conscious choice not to feel the full depth of your emotions right now, because you’re driving or at the grocery store or because someone needs to be the strong one here. Instead, you feel them later. When it’s safe. There’s also the artist’s favourite, sublimation, which is when you make a conscious choice to not react to your emotions, and instead use the energy to do something else, like art or sports.

Humour can allow me to talk about stuff which, without humour, would be uncomfortable for everyone involved. When you make a joke about a painful thing, you get to be honest and direct about the non-negotiable pain we will all eventually have to go through, while neutralizing or lessening the pain of it. People get to walk away from the exchange feeling sympathetic, but also entertained, instead of just feeling gross and sad.

“Dark humour” allows for the free, direct, honest expression of pain. Through humour, we can connect with other people, even when we’re talking about true things that are awful. That is the efferent function of dark humour. Observing dark things with an eye towards what’s funny about it takes the teeth out of darkness, and helps us understand darkness better. This is the thrust behind this excellent video by ContraPoints,2 where she points out that what makes some shock comics bad and other shock comics good is that some people can use humour to better illustrate what’s funny about dark or sensitive subjects. Some are simply not as skilled at doing so. It’s not that there’s nothing funny and absurd about being transgender, to use her example—it’s simply that I’ve never heard the work of a deeply transphobic comedian who actually cared enough about the human status of transgender people to observe them correctly, and as such notice what’s actually funny about their lives. Prejudice and intolerance are, I believe, the result of more immature defensive strategies. To use my terminology, the work of the transphobic comedian has no interesting afferent qualities, and this deficit therefore limits the scope of its efferent capacity.

There are obviously rules in comedy.

Profound pain is not the reason everything that is funny is funny. One theory for a certain kind of being funny is the theory of misdirection: you let your audience think you’re heading in one direction, and then you end up somewhere very different. The gap between expectation and reality creates a tension that is solved by laughing. Then there’s humour that’s basically just cute, where laughter is a delight response to aestheticized helplessness (neutral connotations) and/or agreeableness. I find the Nanalan show endlessly surprising and adorable, and it wouldn’t be so funny if it weren’t also cute. And then there’s your absurd physical comedy, which I firmly believe is funny for the very pure and simple reason that it’s silly. Monty Python’s Ministry of Silly Walks sketch is hilarious not because it’s sublimating some kind of profound pain, or even because it’s some kind of commentary on government inefficiency, but because when people walk funny, that’s awesome.

It has honestly always bothered me when people say that there are no rules in comedy when there obviously are. Usually, what I think people actually mean when they say this is that basically everything in the whole universe of existence—from acts of violence to grief to the nature of God—has at least some absurd element, and as such is something that can be joked about. I am one of those free-wheeling, irresponsible libertines who happens to agree with this, even if I don’t think that means that there are no rules in comedy. I believe that the absurd qualities of a thing are facts of nature, like the weather or the laws of physics, and that sensitivity to people noticing that is the result of a kind of insecurity, or an unreasonable desire to control what cannot be controlled. Attempting to limit what people can notice and laugh at is like trying to stop people from dancing.

I think that these things can be noticed and laughed at in a way that’s cruel, or in a way that’s not. I also don’t think it’s possible to limit cruelty in humour. I don’t think that humour negates cruelty: it was just a joke is not actually a defence against a protest of harm that’s takes issue with the cruelty of a statement, as opposed to its humour. There is, of course, a certain genre of person who thinks that all jokes, by nature of their irreverent qualities, are cruel by definition. As such, they may protest that they take offence to cruelty when in fact they take offence to the fact that anyone would dare to laugh at them at all. This is a very silly kind of unserious person who is too sensitive for the demands of a life on earth, and will surely soon either become stronger or die, and as such is not to be worried about.

I think that something can be cruel and also funny at the same time, because I think that cruelty and humour are independent qualities from one another, and they can belong to the same object simultaneously. I do think that making cruel jokes puts the humourist at a disadvantage, however. Cruelty is lonely. It’s a huge relief for a cruel person to find another cruel person, because I think that most people are basically not cruel and that cruelty has consequences that go right up to life-threatening alienation and isolation. I think that if a comedian makes a cruel joke, there will statistically be some people will definitely laugh. But is it because the humourist is funny, or because they have simply found an effective way to signal cruel people? Do this too much, and one might find oneself with an audience who doesn’t need a joke to be funny at all in order to laugh. I can only imagine a comedian getting worse at what they do in this kind of a situation. I think that this is an unnecessary risk to take. It’s much more practical to practice one’s art without this kind of liability.

I think that you can make jokes about everything, and even do so in a cruel way if that’s a risk you’re willing to take, but I don’t think that means there are no rules in comedy. Or, rather, I’d say that there are rules in comedy the way there are rules in sculpture, or any other kind of art—namely, that art should accomplish its goals, and be good. A joke should be funny. Most comedians would agree that there are expectations and skill sets that go into being good at being a comedian—it is, after all, an art. Art has a craft. I tend to think that if there’s a craft, then there are rules, even if those rules are so instinctive, to the very talented individual, that they’re not all totally obvious.

Jokes are funny when they follow enough of the rules of comedy. When it doesn’t accomplish its goals—when it’s not funny—I tend to think this is why.

But Tara, you may ask, isn’t this quite a subjective measurement?

To which I would reply no, because it’s simple: every joke that I don’t think is funny is not funny because it’s an objective technical failure, and every joke that I do think is funny is successful according to the objective standards of comedy no matter what percentage of the uncultured masses fail to appreciate it. Next question.

Ugh, fine: what I actually think is that there’s there are a lot of things about appreciating art that are subjective, but I still have yet to be convinced that all art appreciation is subjective, because I don’t think that art being good is a measure of whether or not some subjective individual enjoys it or not. I heard someone make the point on CBC’s Commotion3 that the American food environment is a perfect illustration of this: we will consume garbage simply because it is there, and cheap, and goes down easy. A lot of the art and media I happen to enjoy is fucking garbage. It takes me a certain kind of effort to sit through a whole opera. Does that mean opera is bad? Of course not. Why would I assume that what I happen to like and want more of is the objective measure of quality, or value? That would be insane.

So: successful jokes fall into quite a wide margin of styles, many of which are not to my taste. If I don’t think a joke is successful, I think I have an obligation to make sure I’m not misunderstanding something, or not aware of essential context, before I decide it’s a failure. And I think that since humour is a way of communicating, and communication is impossible unless we kinda sorta basically agree that language has meaning based on symbolic representation, and history, and flexible rules of grammar, it’s possible to have a whole emotional or technical reacting to a joke that is objectively wrong, in the way that it’s objectively wrong to decide that Huckleberry Finn is a pro-slavery book because it contains the representative symbols of slavery, to which I may or may not have an emotional reaction that causes an interpretive error.4

But Tara, you may say. Could you not illustrate this with an example?

To which I would reply Of course! Next time. Stay tuned.

This post originally ran June 2, 2025 on Theatre of Cruelty. Visit her Substack now to subscribe.

Specifically, I was introduced to the words as describing the directional flow of motor neurons either towards the central nervous system (afferent) or away from it (efference).

[Eris: Before I’m accused of Discordian revisionism, the official Discordia editorial POV is still anti-ContraPoints.]

I don’t remember who made it, sorry, but if you tell me I’ll edit this!

This is a Green Brothers example. Can’t remember which one.