On the peculiar commodity fetishism that surrounds book-objects

Is listening to audiobooks reading? Are e-books books? Are books just things?

When writing an introduction for a piece, a lot of writers will just sort of lay it down quickly like track before a moving train so they can get somewhere, that being the actual meat of the subject. Well, I’m gonna off-road this train so we can hit this quick: Brian Bannon has a piece out with the New York Times and it’s about whether or not listening to an audiobook actually counts as “reading.” Just about everybody on Substack weighed in, things got cooking, I’m gonna drop some choice Notes about it at the footnote.1 I’m actually trying to get to a topic that’s only marginally-related to this topic as fast as possible because I think it’s more interesting (fooled ya), which you can skip down to if you so choose (it’s the next heading). So, first: do I think listening to audiobooks is reading? Yes.

In his article, Bannon says a friend told him that “listening to a book felt like seeing a musical in New Jersey instead of on a Broadway stage. Close, but not the real thing.” Well, ultimately Bannon’s friend then agrees that audiobooks are indeed reading, because you’ve seen Hamilton whether you’ve seen it on Broadway or in Jersey or at Dachau or at the bottom of the ocean, because all seeing Hamilton requires is that you have seen Hamilton. I don’t know why you would want to see Hamilton, sure, but that is the process by which you would do that. When someone asks you “have you seen My Fair Lady?” you don’t say “no, because I went to a production that wasn’t on Broadway.” What a completely useless comment. Bannon, give your friend a wedgie. New Yorkers, man.

At least 85% of my reading is done off the page. My first read of Madame Bovary was an audiobook—the hilarious drawl the reader gave to Monsieur Léon is still burned into my brain—before I did eventually read it in paper copy. See, in spite of my own assertions, Bannon correctly observes that audiobook-listeners do have a sense of embarrassment about it, even if we believe it’s a valid means of consuming literature. And so I must admit, to defeat my own prideful retort over Bovary, that there are some books I have actually never read in paper copy, such as The Crying of Lot 49 and Neuromancer. But I still consider myself to have “read” those books because when we refer to “reading a book” we generally mean “experiencing it,” and anyone who says otherwise is being deliberately obtuse (unless you think reading braille isn’t reading either). Unless a book has vital formal qualities that necessitate looking at the actual print on the page, you can have that experience when it is read to you out loud. While the two experiences—listening and literally reading—are still experientially distinct, they are not so distinct as to make listening invalid. I prefer to literally read a book with my eyes; I often find it to be a more enjoyable experience—this is where the Broadway analogy does come in. You’ve seen Hamilton no matter where you’ve seen it, but you’ll probably have a more engaging time of it on Broadway. Well, hypothetically, anyways. It’s still Hamilton. But the origin of literature isn’t written, it’s spoken, literature began with oral tradition. The great epics of antiquity were rhapsodized. The “written word” is older than the literal written word. It’s still reading, because “reading,” as in consuming literature, predates the act of literally reading.

Another important point—some people’s literal process of reading is distinct, like phenomenologically. When I read a book, I often hear the words in my head—I can reduce this consciously in order to read more quickly, but I prefer not to because the sound of language is part of why I read, so in a sense I am in fact always “listening” to literature in some way or another. Some people don’t or can’t hear the words at all. Some people visualize more than others. The foundations of the reading experience are thereby fundamentally built with different materials in different people’s heads, making this debate extra silly. And as for the people arguing that they can think more deeply or engage more deeply when reading off the page themselves… I dunno, I think I just have different processes of engagement between the two. I tend to do more thinking in tandem with the text when I’m listening, for instance, and it can be interesting to form a thought about what I’m hearing as a sentence itself develops. It’s just different.2 Again, I personally prefer to read on the page, as there’s a certain satisfaction and quietude that reading off the page lends you that is lost when listening to it read aloud,3 but I don’t think that experience is itself integral to the act of experience of a work of literature in-and-of-itself.

The real topic: book fetishism.

So, I said “off the page” and “paper copy” back there a few times, but the truth is those phrasings were… perhaps misleading. Because the truth is, of the books I read with my own eyes, I read the vast majority of them in e-copy, either on one of my multiple e-readers or on my desktop via Calibre. It’s just more convenient for me, feels less burdensome (I have dainty little wrists!), I can keep track of my notes and highlights far more easily, and—as I’m usually reading four or five different books at any given time—it’s space efficient for when I’m travelling or commuting. The amount of flak I still get from certain book people about this is absurd. Why does it bother them so much? The answer is something I think may be the real key to understanding the audiobook debate as well—the peculiar commodity fetishism of books.

Books are treated as moral artifacts, their mere existence serves to reinforce certain societal values, such as literacy, enlightenment, curation of knowledge, etc. They wind up going beyond mere containers of meaning to highlight the importance of meaning in the abstract. Then, so-imbued, we turn them into proxies for personal value in accruing them—who else has heard the cringey dating advice “if they don’t own any books, don’t fuck them”? The book becomes imbued with a powerful aura, but this aura obscures the book’s material reality. You don’t have a priceless scroll from the Library of Alexandria in your hands, you are holding a mass-produced commodity, printed in a factory by underpaid workers, shipped to the store, and sold to you for a profit. But the aura of the book is perhaps stronger than any other commodity’s aura in blinding us to this fact. Strange as it is, it seems almost impossible to imagine a mass-market paperback as a product of labour.

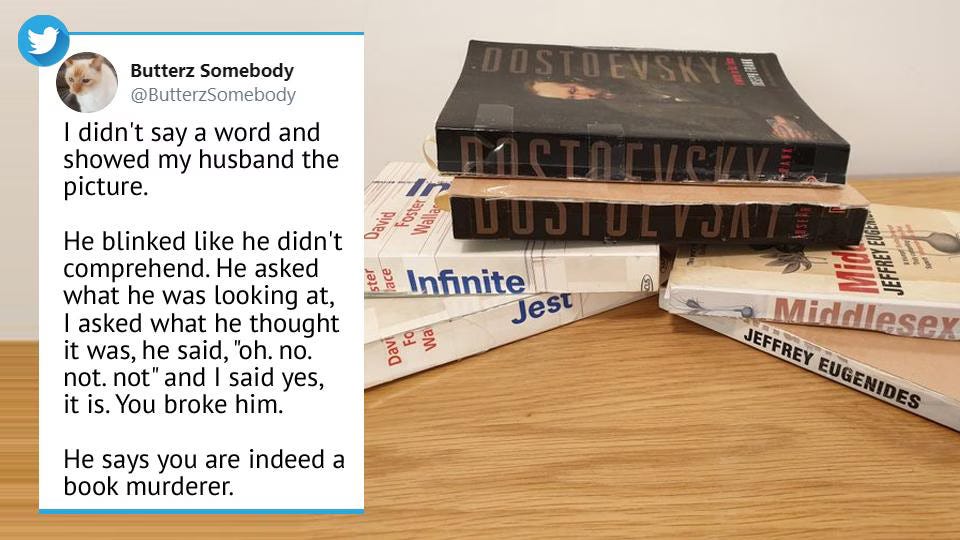

It feels sometimes like, at this point, when a bunch of crypto-fascists start burning books, people mistake the crime for being the destruction of the sacred book-objects themselves and not the wider meaning regarding fear-mongering, maintained ignorance, and social control. Remember the performative explosion over this image?

The man who owned these books allegedly ripped them in half in order to make reading and transporting them more convenient. People got very worked up about it. In all likelihood he was just trying to get a rise out of people, but like, why did it work? Who cares what he does with his copy of Infinite Jest? It’s his. He bought it. It probably cost him $15. You can find your own copy in literally any bookstore in the world. It’s worthless. And this copy is even still readable!!! You can still literally use it for its intended purpose!!!

The object is just the vehicle, but by the way people act it’s almost as if the book-object is more sacred than even its contents.4 Book-objects take on a sort of role for a lot of people like bacon did to internet users in the late-2000s—bacon is “epic,” bacon “makes everything better,” zomg epic bacon, bacon is my favourite thing evarrrr. Part of this may also be the performative ritual of reading, the act of opening up a book, of feeling it’s spine in your hands, and what it does to how we see ourselves or imagine how we are seen, whether we are seen in public or imagining it. When you consume a book via e-copy or audiobook, you lack the theater, the performance of reading a book. I think many people are afraid to admit they have a certain pride in being seen reading, that the book-object is a means of projecting their valour, of showing it to other people on the bus. I once posted in my Instagram story: “nobody can see how smart I am because I’m reading Lefebvre on my phone :( :( :(”—I was only sort of kidding.

There are few things which confer identity better than the book-object. As coldhealingput it in a piece a couple years ago:

Because book-objects are portable and self-contained, they allow for powerful curation of identity. You can carry around a copy of Infinite Jest, and at any point you could be reading it. Now you are the type of person who reads Infinite Jest and the people around you know that and you know that they know that. You can kill John Lennon and be holding a copy of Catcher in the Rye and read it immediately after the murder, and that says something about you.

And that value, what that says about us, is of immense import, and in an increasingly illiterate world, wielding a book of any kind begins to confer one particularly powerful meaning: I’m better than you.

But I can’t pretend to be above anybody here, because of course in spite of everything I have just said, I also have my attachments to book-objects. My apartment is filled with them. My wife and I have a 4x4 IKEA Kallax bookshelf filled end to end with books, only they’re stacked in double rows so half the books are behind the books in front of them (alphabetically the front rows continue into their back rows) and then there’s also books stacked sideways on top of those books. We then have a thin IKEA Hemnes bookshelf with the same situation. I have a wooden pallet leaning on the wall which serves as yet another bookshelf, and it’s a disaster, and both my wife and I have bedside tables that have more books than table, and we’ve had to resort to filling some drawers in our house with extra books, it’s getting that bad. And of course we can’t get rid of the damn things, because we’re a couple of hopeless book fetishists! I can’t get rid of this biography of Robert Lowell I’ll literally never read! It’s a book! And it’s in my house!

Freddie deBoer weighed in on the affirmative:

Followed by The Literarian Gazette in the negative:

…then Philip Traylen with the rebuttal…

…and Udith Dematagoda with something sort of in-between:

…while I was particularly partial to this one from Michael Shull:

And some readings change my experience of a text when done by others! I once got to hear Marina Carr read from Woman and Scarecrow live and it completely changed my experience of the written work itself.

Sire: One might add here that reading on the page allows one to control the pace at which one is taking in the information in a way that listening does not. The voice actor (and/or producer) performing an audiobook is also making decisions about emphasis, tone, and characterization that would otherwise take place within the reader’s mind.

Sire (again): I’m reminded here of a conversation I once had with antiquarian bookdealer Nicky Drumbolis in Thunder Bay, Ontario, who called his shop “a tribute to the fetish object formerly known as the book.” I wrote about him, and my own mania for physical objects, a few years ago:

To Drumbolis, the original utility of the book as a container and mediator of information is now effectively outmoded; virtually every popular book in existence has been digitized, their contents instantly available in formats that are better-indexed, more easily parsed, and more readily transferrable than the humble physical book ever allowed. To desire a book is to desire possession of the thing rather than its contents, this edition, this printing, perhaps this particular copy that once passed through the hands of someone significant.

Drumbolis, a man whose collectivitis is so advanced he moved from Toronto to a remote Northern Ontario community with no literary culture to speak of because it allowed him space to store all of his books, is diagnosing a more boutique version of what Eris is onto above (most of the ‘books as accessories’ types lack the real knowledge of deep publishing nerdery that fuels a true book fetish). But it does speak to how the past thousand-or-so years of print culture have imbued physical books with a quasi-mystical (and thoroughly class-coded) significance. I shudder when I see good books mistreated, and have gone out of my way to “rescue” them even when they are of no use to me.

In her “Short Lecture on Evolution” Mary Ruefle wrote, “A book is a physical expansion of the human brain. It is not an object to be treated lightly. When you hold a book in your hands you are holding a piece of cerebrum in your hands, like Saint Denis himself, who walked for miles carrying his own head in his two hands, after he had been beheaded.” That feels right to me, even as the same statement is technically also true of a USB drive, an object that doesn’t elicit much sentimentality. (I’m also reminded of Geoffrey Nutter’s wonderful elegy for the telephone book, that bygone exemplar of utilitarian printmaking.) The real truth of our attachment is, perhaps, that in partaking in the act of physically reading a book, we are performing reading: what was once the dominant method of experiencing literature becomes a preference of long habit; becomes, in those born in the screen age, a self-conscious statement. But it is not necessarily a statement being made for an outside audience—true romantics perform even in solitude.

I like this analysis, and the idea of the book as fetish object makes sense to me. I tend to prefer thinking of books as having a symbolic function (an object that points to the human labor that created it, the tradition of the genre, etc…) At the same time, the difference between a symbol and a fetish object can be slippery. Symbols can be abstract enough that they also need to find some grounding in material reality, and when they do it’s easy enough to turn them into a fetish.

Books as external brain makes sense to me also in the sense that one's library is a more complex fetish-object than a single book is; like a book-temple, a conglomeration, an arrangement of sets of ideas... You might not even open the books you own very often, but looking at their spines helps you to think, & to remember what the fuck you're on about... I say this as someone whose library has been packed away in boxes for a year, making it much harder to think.