Maggie Nelson's new Taylor Swift/Sylvia Plath book is an embarrassment

"The Slicks" is a blatant attempt to mask standom as serious cultural critique.

Earlier this year, it came to my attention that Maggie Nelson, one of the most lauded writers of her generation, was writing a book about Sylvia Plath and Taylor Swift. This seemed like a rather ill-advised project and I obviously expected, as I’m sure many people did, that the book would suck. But I was not prepared, I don’t think anyone could have been, for… this. I grabbed a copy out of morbid curiosity, and within a couple of pages I knew that this post simply could not wait. I had to write about this immediately. Reader, if you haven’t experienced this book, then I don’t think you could possibly understand just how bad it is. In a meritocratic literary world, this would kill Nelson’s career on the spot. The Slicks is a book so baffling, a book so fucking stupid, that it places the entirety of the rest of Nelson’s oeuvre into disrepute by mere association. I, for one, will never take Nelson seriously ever again.

Let us first get one thing right out of the way: this book is not about Sylvia Plath. This book is, in reality, entirely about Taylor Swift, and Plath, in spite of having her name first in the subtitle, is really just relegated to a supporting character in Taylor’s story. Plath is instrumentalized to provide legitimacy by association, to present Taylor as being in line with Sylvia fucking Plath, a woman who probably sits right next to Emily Dickinson as a contender for the world’s most celebrated woman poet.1 There are very few women in literature who enjoy such widespread acclaim and adoration. As Nelson mentions in the book, she has met little girls—children—who know Plath’s name as something synonymous with poetry itself. She is a titan, a god, unassailable regardless of any individual’s personal opinions of her, such as if one *ahem* actually prefers the work of her husband. I know a poet who is a trans man who once joked that he transitioned “to escape the shadow of Sylvia Plath”—one can scarcely think of a more grandiose point of comparison. Why else choose Plath? What do Plath and Taylor actually have significantly in common? Surely Nelson, who chose to make that comparison the supposed premise of an entire fucking book, could provide at least some kind of legitimate justification for the move. Spoiler: no! Not at all!

I’ve surprisingly written a lot about Taylor Swift on this uhhhh ostensible literature blog, but that’s sort of a product of Taylor trying to insert herself into “literary spaces,” and here Nelson is effectively working in much the same capacity as a Scientologist buying up copies of the latest dogshit Hubbard novel: they are working tirelessly to bolster the ego of their respective master by fulfilling said master’s fantasies. Taylor wants to be in the literary conversation, so here is her deluded literary acolyte answering the call to support the Supreme Leader. Taylor Swift is actually an inspiring literary figure belonging in the same conversation as Sylvia Plath! And from the age of two she could golf a perfect game!

Nelson tries to make it seem like this isn’t her comparison, that it’s an obvious comparison, really. Plenty of people are saying it! Taylor herself is allegedly making allusions! Says Nelson: “[Taylor Swift]’s lyrics and self-presentation, as many have noted, make nods to Plath.” Ah yes. Using “many” is a rather sly move here because you get to vaguely rely on some sort of multitudinous authority without citing those authorities (and revealing how nebulous their “authority” really is to make the comparison) or quantifying just how “many” there actually are in the first place, a classic gambit—and of course “nods” can also do quite a bit of legwork, turning an absolutely unfounded assumption into a suggestion merely of a refined “subtlety,” a knowing “gesture” that Taylor is simply too restrained to make explicit. But Nelson cannot help herself, because before the paragraph is over she jumps from suggesting a “nod” to a full EXPLICIT reference. See, according to Nelson, Taylor “EXPLICITLY [emphasis my own] merge[d] Plath and Dickinson iconography” in her music video for “Fortnight.” The basis of this claim? In the video Taylor is institutionalized and receives ECT (Plath) and is wearing nineteenth-century dress (Dickinson). How EXPLICIT!!! I would like to first point out that institutionalization and electroconvulsive therapy are very common tropes throughout media and culture (the fucking Simpsons received ECT), but also the “nineteenth-century dress” Taylor is seen in looks like this:

…Whereas the only extant depiction we have of Emily Dickinson has her dressing like this:

…Which you may notice looks absolutely nothing like what Taylor is wearing. So I suppose Nelson believes it must be a Dickinson reference simply because it’s vaguely “Victorian,” but then why stop at Dickinson? Why not any other nineteenth-century woman poet, like Elizabeth Browning or Christina Rosetti? Hell, why not claim that Taylor is alluding to every single nineteenth-century woman who ever lived, since, golly, if just wearing nineteenth-century dress constitutes such an EXPLICIT reference to Dickinson just because she happened to live through that period, surely it must be equally as valid to read it as an EXPLICIT reference to literally any other woman from the same era!

I’m really surprised that Nelson doesn’t do more with the Dickinson comparison, might have made a great opportunity to enter some Gaylorist territory—considering how shameless she is with the Plath comparisons, why not? I mean, just look at this shit:

Both [Plath and Swift] evidence [sic] a nearly superhuman ability to perform or create under great pressure, albeit of distinct varieties. In both cases, there appears to be a fruitful struggle—recognisable to most artists—between form and flow, superego and id. Plath’s poems are […] famously tight. Likewise, it makes no sense to call Swift’s songs ‘excessive’ in and of themselves; most are perfectly orderly pop songs, hovering around four minutes in duration.

???? LIKEWISE??? How is that LIKEWISE????? Taylor Swift’s pop songs have pop song lengths, and that is somehow like how Plath’s poems feel tightly controlled. There is nothing analogous about these two qualities, nothing at all, yet Nelson dedicates a paragraph to waxing on it. Even when talking about how the two are disanalogous, Nelson chooses to try and make the contrast “mean” something:

Some may express incredulity or irritation at the repetitiveness of Swift’s paeans to falling in love and subsequent heartache, but when placed beside the severity of Plath’s ‘it’s gone forever’, the repetitiveness can be quite heartening, even comic relief. What goes on forever, in Swift, is giving your whole heart, feeling or fearing that it will never come back, then having it return, maybe even despite itself, then being foolish enough to do it all over again (and again, and again).

Nelson is just describing the limited range of pop music subject matter. This, like the length of Taylor’s songs, could describe the work of almost any pop act—pop artists write an endless parade of songs about love and heartbreak. I could get this same experience from my mother’s Carpenters records, it’s not a meaningful statement about anything at all, it’s a decision born out of commercial appeal. But Nelson simply cannot help but attempt to frame every innocuous and compulsory detail of Taylor’s career as being weighty and original:

Not unlike Swift, whose songs often pay homage to a male beloved, Plath often imagines herself in thrall to—and/or crushed by—a male beloved, father or god.

Wow, they both write about men???2 Again, we must ask, how does writing about men make Taylor any different from any other woman pop star (aside from the new crop of gay ones, I guess)? Nevertheless, take any of those pop stars who write about men and try to make writing about the subject a point of comparison to Plath, and you really miss that the key (and rather obvious) distinction is in how Plath talks about this topic. That is what distinguishes her from someone like Taylor Swift, the actual insights she brings to the table, the language she uses.

Beyond just the Plath comparisons, the book is filled to the brim with eerily-obsessive fawning praise:

I celebrate Swift’s genius for pop, her apparent sanity and joy-giving capacity, her ability to feel and express a wide range of positive and negative emotions without circling the drain

For instance, one repeated point Nelson harps on is the volume of Taylor’s work, her sheer fecundity as a songwriter—wow, she dropped an additional fifteen songs within hours of releasing Tortured Poets Department! Nelson misunderstands that this prodigiousness is not an artistic statement, it’s a ploy to exploit the streaming economy, and artists like Drake (who has used the tactic to chart 359 songs on the Billboard Hot 100) do the same thing.

Granted, at least once or twice, Nelson is willing to give an ever-so-slight concession to Taylor’s critics:

It could be fairly argued that, far from being in danger of suppression, Swift has achieved global domination,3 and that, in a world increasingly defined and brutalised by inequality, it’s only fair to feel antipathy for its biggest winners, especially of the normative (straight, white) variety.

…but of course you know that “but” is coming:

But I still think it behooves us to pay attention to how Swift’s profusion and power provoke round after round of resentment, animosity, and threat—most obviously in MAGA/incel circles

For you see, it BEHOOVES us, we are simply BEHOOVED, to pair any discussion of Taylor Swift with a consideration about how contempt for Taylor Swift, a billionaire whose lavish lifestyle ensures other less fortunate people die in the street, is somehow indelibly tied to MAGA and incels. Even after simply saying “nobody has to like or listen to [Taylor’s music],” she nevertheless says:

it’s worth asking what we’re doing when we express distaste for female abundance or power; it’s worth asking what idea of human order might enable us to celebrate such a phenomenon without the fantasy—or reality—of its castigation, suppression or elimination.

Yes, you see, nobody HAS to LIKE Taylor Swift, but apparently we HAVE to do at least THIS, we HAVE to qualify every criticism of Taylor Swift with THIS bullshit, it’s our RESPONSIBILITY to couch every criticism of Taylor Swift—of her music, of her cultural impact, of her billions of dollars—in these painful excuses. What kind of “human order,” asks Nelson, would “enable” us to “celebrate” someone having so much while others have so little without the “fantasy” of that privilege’s “elimination”? Here, Nelson seems to suggest that a society which could faultlessly protect Taylor’s privileges—not just from dispossession, but even mere scrutiny—would effectively be a utopia.

“No one has to like or listen to it,” says Nelson, but is there literally anything at all one can be allowed to say about disliking it or not wanting to listen to it? Nelson should ask herself: just what criticism of Taylor is valid? For instance, she gets extremely mad at Ross Douthat for having simply that said that, if Taylor was going to release so much material—albums with like thirty songs!—she could at the very least sometimes write about something other than herself:

My prescription is that if Swift is going to be this prolific, she needs more leaven in her content. The core of her brand will always be the personal drama of Being Taylor Swift, but that story’s cycle of infatuation, love, rapture, disappointment, pain, revenge has hit a limit of interest in her current work. [I will add that he was suggesting this specifically in response to that album’s rather tepid reception.]

Allegedly, Douthat said this “to the delight of precisely no one” (per Nelson), which is a rather harsh thing to say about what seems to me to be a pretty inoffensive opinion on the most dominant and oversaturated musician on the planet. Maybe she could pen us a song about, oh I don’t know, Buckaroo Banzai or something. But no, Douthat is surely being “sexist” because he’s getting sick of being assaulted by Taylor Swift’s tabloid circus. More interesting to me, however, is Douthat’s more recent piece on Taylor Swift, which does not appear in Nelson’s book, and discusses Taylor’s most recent record:

[In] the current cultural moment, however you run the polling, the impulse to elevate marriage and kids as core life goals is much stronger on the right than on the left, as are heteronormative life scripts and the actual practice of heterosexual marriage. So singing about how “when I said I don’t believe in marriage that was a lie,” or expressing a newfound desire to “have a couple kids, got the whole block looking like you”—or for that matter, celebrating male endowment in a song called “Wood”—is inevitably conservative-coded, even if the singer undoubtedly voted for Kamala Harris.4

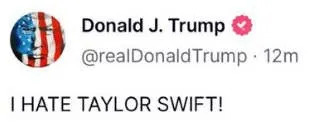

See: for all Nelson’s claims that Taylor Swift is a ubiquitous target of MAGA for being a “powerful woman,” she neglects to mention that the biggest reason for this was Taylor’s own comments about Trump, which is why Trump famously posted this:

Since Kamala’s failure, Taylor has been notably mum on the subject of ol’ Donnie. In fact, Taylor has grown closer and closer to rather avid Trump supporters like Brittany Mahomes and Dave Portnoy (who is also a pro-lifer who has been accused of sexual assault by three different women! Very cool!), and claims her favourite podcast is Bussin’ with the Boys, featuring Taylor Lewan and Will Compton, also vocal Trump supporters. I don’t really think being friends with or associating with people who are MAGA necessarily makes you MAGA in turn, but someone like Taylor is pretty obviously aware of the optics of someone in her position doing so and chooses to associate anyway without comment—to say nothing of the fact that Taylor Swift hasn’t said a word about Trump using her song “The Fate of Ophelia” on social media. I wonder if this has anything to do with her lyrics on the new album about how she “likes her friends cancelled.” Aw jeez, I guess there goes Nelson’s thesis, huh? And just a few weeks before the book even came out! Talk about bad timing!

One of the most remarkable things about this book is how willing Nelson is to just take everything she sees of Taylor at complete and utter face value. It’s hopelessly naïve—is Nelson writing in bad faith or is she just that simple? Look: like many people, I am quite impressed by Dua Lipa’s literary interviews, and I certainly feel like these interviews are a genuine expression of Dua Lipa’s own interests—but the thing is, I can’t know for sure, because this is Pop Star Land we’re talking about, a realm of sheer simulacra, and it’s just as likely that Lipa has some marketing people who decided that having her image be that of a well-read intellectual would be good for business. Her Charco Press picks could have been chosen for her. Her interview questions could have been fed to her. We just don’t know. This much I can say for certain though: she absolutely wouldn’t have done it had her marketing people thought it was a bad business decision. Nelson doesn’t seem to get this, and doesn’t exercise an ounce of skepticism over any element of Taylor’s branding. She marvels, for instance, at Taylor “writing (or co-writing) all the songs on her eleven albums,” but let’s be real, we can’t know how much input Taylor has actually had on those records. If she’s such a “gifted” songwriter, why does she even need all those collaborators anyways? There isn’t a single co-writing credit on Joni Mitchell’s Blue; say, how much “co-writing” do you suspect those “co-writers” of Taylor’s are actually doing? Plenty of pop “songwriters” have been exposed for lying about writing their own songs—Beyoncé, for instance—ask yourself, do you really think Taylor isn’t one of them? And if you don’t, do you have a reason for this conviction beyond “I just like Taylor Swift”?

Let me demonstrate my point with an even more direct example. At one point Nelson quotes Taylor in an interview saying she is “never” freaked out by her own fame. Nelson’s reaction:

I don’t typically take what people say to interviewers at face value, but I’m nonetheless riveted by It never freaks me out. Never. Ever. I’m riveted by it because it points to one of the rarest things about Swift, which is how good she is at being famous.

There’s a lot to talk about here—why as excessive an adjective as riveted for something so banal? And what does she mean when she marvels at “how good” Taylor Swift is at being famous? Because it’s always sort of seemed, even as someone like myself who doesn’t pay particularly close attention, that Taylor is actually extremely neurotic and thin-skinned. Most importantly, however, is that Nelson says “I don’t typically take what people say to interviewers at face value,” and then takes what Taylor Swift says exactly at face value, and then never explains why it is that she has done this. What makes Taylor Swift more trustworthy than any other person? Nelson never questions this assumption on her part—a line of introspective intrigue which would have, frankly, made for a much more interesting book—because she does not realize that she has become a member of a loosely-affiliated cult, someone willing to sacrifice all of her own alleged convictions or principles for the Glory of Taylor.

Take, for instance, the consideration of Taylor’s wealth itself—Nelson claims that, per Forbes, Taylor Swift is “the first musician to [become a billionaire] from songwriting and performing alone, no ‘side hustles’.” But Taylor’s billions obviously are not just the result of the profits of her music itself. She likely has a vast investment portfolio. We know, for instance, that she commands a large real estate empire that makes her hundreds of millions of dollars. Say, does Nelson consider “landlord” a “side-hustle”? I guess it’s not really “hustling” when the income is entirely passive. The underlying assumption to all of this, of course, is that Taylor “deserves” this money, that she “earned” it through her hard work and talent. That sort of sounds like the sentiments of someone who loves and appreciates capitalism, not someone who, for instance, responded to Fifty Shades of Grey by saying this:

“Some gnarly capitalist?” Nelson said, rolling her eyes. “That to me is super not hot! Super not hot!”

Well, which is it, Maggie? Were you just lying because you wanted the Guernica writer to think you were on the level? When you go back through Nelson’s work, or even just the previously linked interview, you find that most of her “criticisms” of capitalism just amount to some belief that capitalism is inherently antagonistic to queerness, which it isn’t, in fact queerness is easily co-optable by capitalism and poses little to no threat to it at all so long as the underlying class relationships to production and power are maintained—faux-leftists are always misunderstanding this, and are as such often ignorant of the fact that they themselves are just liberals. However, I do believe that Nelson at least believes she is antagonistic to capitalism, and that capitalism is antagonistic to her queerness. And yet when Taylor does it… capitalism becomes good, actually! Impressive! Laudable even! Other times, it is merely a point to be discarded:

Some people5 grouse that Swift’s artistry is tainted by its being the engaging of a billion-dollar industry, and that her creativity cannot be considered apart from capitalism. Sure—but welcome to the world of pop music, it ain’t poetry.

Nelson refuses to engage with the argument at all, because this is “the world of pop music, it ain’t poetry.” But then what the fuck is this book? Why compare Taylor to Plath, or insist with very little evidence that Taylor is drawing comparisons of herself to Plath—why would any of this matter? It ain’t poetry! Except that, do we actually think that Nelson believes that? Reader, after having gotten this far, do you think that sounds like a position Nelson actually supports? Obviously not. Everything we have thus far read supports nothing less than the idea of Taylor as a genius on par with if not exceeding any pedestrian “poet.” Just read how Nelson chooses to talk about Taylor’s “Eras Tour”:

It’s this going on and on in increments of song—and album—that has led to one of Swift’s greatest innovations: the Eras Tour, which cannily merges lyrics and epic traditions, transforming both by rooting them in girlhood and womanhood.

Epic traditions??? This woman is trying to claim Taylor Swift is in the same tradition as Homer. Even the rather inconsequential fact that the “eras” are presented in non-chronological order is treated like a fucking revelation:

[T]he eras do not unfold in chronological order, Swift wants them to appear for the purposes of the show. This is the radical takeaway for legions of her young fans: the story of your life is literally what your art makes of it.

Huh???????????? How else are we supposed to respond to a statement like that? It’s idiotic. Anyone could tell you that. It’s embarrassing. And yet, if we raise our eyebrow so much as a fraction of a millimetre (and believe me, my eyebrow was starting a new space agency in order to take a voyage to the fucking moon) in response to any of Nelson’s claims, she again hits us with a line like:

Last time I checked, Swift was not angling to be a great poet.

Which is just so fucking disingenuous! Not only does it seem rather obvious that Taylor would like to be seen in that light, it’s even more obvious that Nelson thinks that’s the case. Taylor Swift is a great poet! aha ha, just kidding… unless? 🥺👉👈 Nelson wants to compare Taylor to Plath, but wants to be able to do so with plausible deniability in case you call her on how patently ridiculous such a comparison is. But she’s terrible at it, she has no poker face, she can’t control herself when she’s talking Taylor. In spite of all the half-hearted denials, she’ll write shit like this:

When I think about Swift and Plath together, I find myself returning to a simple thought: Sylvia Plath is dead, and Taylor Swift is alive.

Which sure reads, rhetorically, like the assumption must be taken that Plath and Swift are interchangeable, it’s merely that one of them is dead and one of them is alive—the juxtaposition allows proximity to do the work to fill in the gaps. Nelson, a career essayist, should recognize as much, or else she’s just writing sloppy. So which is it? Well, we don’t need to even ask, because the next thing you know, Nelson is explicitly comparing them line for line!

When Swift sings ‘he was sunshine / I was midnight rain’, I hear Plath excoriating her mother, ‘Don’t talk to me about the world needing cheerful stuff.’ When Swift sings ‘making my own name, chasing my fame’, I hear Plath’s furious vow, ‘I will slave and slave until I break into those slicks.’

Do you really hear those things, Maggie? Because I certainly don’t. Let’s actually compare Swift and Plath at length, shall we? Here’s two poems more or less concerning the same subject: mirrors and identity. Here is a section from Taylor Swift’s “Mirrorball,” off of her most “writerly” album, folklore:

I want you to know

I’m a mirrorball

I’ll show you every version of yourself tonight

I’ll get you out on the floor

Shimmering beautiful

And when I break, it’s in a million pieces[Chorus]

Hush, when no one is around, my dear

You’ll find me on my tallest tiptoes

Spinning in my highest heels, love

Shining just for you

Hush, I know they said the end is near

But I’m still on my tallest tiptoes

Spinning in my highest heels, love

Shining just for you[…]

Because I’m a mirrorball

I’m a mirrorball

And I’ll show you every version of yourself tonight

And now here’s Sylvia Plath’s “Mirror,” one of her “lesser” poems:

I am silver and exact. I have no preconceptions.

Whatever I see I swallow immediately

Just as it is, unmisted by love or dislike.

I am not cruel, only truthful‚

The eye of a little god, four-cornered.

Most of the time I meditate on the opposite wall.

It is pink, with speckles. I have looked at it so long

I think it is part of my heart. But it flickers.

Faces and darkness separate us over and over.Now I am a lake. A woman bends over me,

Searching my reaches for what she really is.

Then she turns to those liars, the candles or the moon.

I see her back, and reflect it faithfully.

She rewards me with tears and an agitation of hands.

I am important to her. She comes and goes.

Each morning it is her face that replaces the darkness.

In me she has drowned a young girl, and in me an old woman

Rises toward her day after day, like a terrible fish.

Come on, Maggie. Be fucking real. But I don’t know, maybe this is her “real” now, maybe she’s just that far gone. I mean, look at this sentence she writes sincerely about her feelings for the song “Clara Bow”:

The first time I heard this song, I felt immeasurably sad. I think it was the repetition of the word ‘die.’

Did you laugh at that, reader? I know I did. Loudly. It was at that point that I stopped and began flipping back through the pages I’d already read, desperately trying to determine whether or not what I was reading was just a work of satire. I found myself staring at this earlier Nietzsche quote that Nelson cites while attacking critics longing for depersonalized work:

“[I]t has gradually become clear to me what every great philosophy up till now has consisted of—namely, the confession of its originator, and a species of involuntary and unconscious autobiography.”

Yes, I’d say such slippage is very much on display here. Just take this next line from Nelson. I don’t even remember what it was referring to. At this point it doesn’t even matter:

It’s corny, sure sure, but its capacity for deflation also feels potentially life-saving.

This sentence could stand-in as a microcosm of the whole book. Falsely undercut, immediately making way for a lofty and hyperbolic claim. You can see that there is something inside Nelson, a voice meekly squeaking for this façade to be pulled down, but something fiercer, something stronger within Nelson, something obsessive and ugly and deranged, is holding the source of that voice down and strangling it.6 You know Nelson can still hear those dying whispers echo in her head, and as a result I think Nelson is at least a little embarrassed about the project on some level considering she chose in one interview, in an act of deliberate minimization, to refer to the thing as “a little zine”—Maggie, I co-run a zine press, I know zines, and this is what we in the industry call a “book.” Penguin Random House is not a zine distro. I really don’t blame her, though, I’d be embarrassed too.

It isn’t as if Nelson hasn’t been in decline already. Her last original book, On Freedom, wasn’t particularly good. Not only did it fail as a work of political analysis (Nelson misunderstands quite a bit of her subject matter, especially—and most offensively to me—Marxism7), but it also fails as a work of literature, being a rather dry and pretentious work of self-impressed sipping from such a shallow chalice. It’s funny that Nelson writes so often about women being castigated for their emotional outpouring when her own work has so clearly lost the heart it once possessed in books like Bluets in favour of this increasingly depersonalized chin-stroking. It’s a trap that acclaimed artists of all stripes may fall into—you get enough praise for your “genius” and the next thing you know you think you’re a philosopher (I wrote about this before with regard to Arcade Fire and Kendrick Lamar)—but it’s a path Nelson seemed destined for since, even on her “better” earlier efforts, she was walking a very fine line on the border of complete self-indulgence. In her review of On Freedom, the late Rachel Cooke aptly put it that “rarely have so many words been used in a supposedly non-academic book to so little effect”—The Slicks has continued this trend exponentially. No, that’s not fair, they do have an effect this time, it’s just that it’s an effect entirely counter to Nelson’s own points.

I’m not the only one to be frustrated by Nelson’s new book, and I shan’t be the last. Becca Young wrote a piece in Defector where she rather succinctly put the problem here:

As I read, I found myself increasingly frustrated. I had just read The Argonauts for the first time this year, and was amazed by Nelson’s capacity for reflection […]. This book—which cries “misogyny” at the mere hint of suspicion toward her primary subject—feels less like an exploration of contemporary feminism than an exercise in contemporary fandom. That she claims thinking Swift’s album is too long is a symptom of the same “feral misogyny [as] the MAGA movement” and the “overturning of Roe v. Wade”; that she brushes aside critiques of Swift’s wealth; that she compares Swift’s artistry, and suffering, to that of Plath at all, demonstrates a kind of jaw-dropping lack of perspective that betrays the reader’s trust.

That last sentence especially had me nodding feverishly. Yes, the book’s perspective does “betray the reader’s trust.” It is such a flagrant betrayal, so callow and obvious as to be an insult. We’re expected to sit here and swallow this? Yes, it’s evident that Nelson thinks quite highly of herself, but does she really think so lowly of the rest of us? What an astronomical waste of time this constitutes for Nelson’s audience, even at this meagre length. I look at all this, and… FIFTY PAGES. Is Maggie Nelson OKAY? FIFTY. FUCKING. PAGES. Of THIS. How STUPID, how DELUSIONAL, how IGNORANT, how ARROGANT, how DESPERATE, how PATHETIC, how LAZY, how BANAL, how SHALLOW could you POSSIBLY BE? FIFTY PAGES. This read like the worst Slate article in the world. Except that even Slate thought it was stupid. FIFTY FUCKING PAGES! Oh it’s “The Slicks,” alright, a slick handful of shit spread across the fucking page, possibly the worst book by a major author to come out all year. This is little more than fandom, sheer pathetic hero worship, made only the more pathetic because this woman’s hero is such an unheroic void of a person who is also twenty years her junior,8 turned to desperate propaganda in a vain attempt to get us to join her in this embarrassing display. There’s still time, Maggie. You can still come out and say “sike.” You can play it all off like it was just a joke, and hey, maybe even if we weren’t dumb enough for this charade of a book we’d be dumb enough to at least fall for THAT. A retraction, a penance, a public flogging, anything—this crime against literature cannot go unaddressed.

Nelson is not the only victim of Taylor Cultism, the conditions of which I have discussed before:

Madonna’s humanity was available to us through its inversion: the material of the Material Girl was a façade, and with enough licks one might find the real girl at its center. The presence of humanity was implied among the plastic. Swift, by contrast, is the Immaterial Girl. Sincerity and authenticity is her primary marketable gimmick. Like wax fruit or Subway sandwiches, the utility of the “material,” of the plastic substance on display, is to trick you into thinking it’s anything but. The inversion, the “true” Taylor within, is a pneumatic vacuum. What makes the product so particularly successful is that Taylor, or more appropriately her handler, has allowed her audience to fill that vacuum with whatever they please.

A friend of mine sent me a deranged post in which a Taylor fan speculated about Taylor’s religious faith, resorting to fantasizing about how incredible it would be to die and be with Taylor Swift in heaven as she leads worship. Madonna’s name evokes the divine, but it’s ironic, it’s effectively anti-religious; Madonna is the rejection of the authentic and the sacrosanct. But sincerity, however actually insincere, is Taylor’s whole brand, and this naturally leads, at this apotheosis, to religiosity and pseudo-divine experiences, the ultimate expression of a spiritually-bankrupt culture seeking an outlet, a search for God in a post-megachurch world. Like megachurch Evangelicalism, it is religion without the mystery; it is the sphinx without the riddle, and it is the poverty of the soul in a commercial culture that has carried out the theft of the worshipper from God himself.

This Taylor cult even has its own eschatological ideations. At one point in The Slicks, Nelson imagines the end of Taylor Swift as if it’s the end of the world:

Nothing lasts forever; at some point, even the bounty of Swift’s songs will no longer seem like enough. People will rue that the pouring is over; the wish to ‘burn away all the peripherals’ will be replaced by a scouring of the archive, just as Plath’s archive has been the subject of intense revisitation for decades now, with no sign of letting up.

Mm, Nelson would like to think so, I’m sure. Over Thanksgiving my cousin (a Swiftie) and I (not) polled our family’s innumerable runts popped out in the last decade for their opinions on Taylor Swift. They all said they hated her. Stupid old people music. They much preferred pop girlies like Addison Rae or Olivia Rodrigo. I doubt Taylor will ever “go away,” she’ll likely sell arenas until the day she dies, but even the fainting religiosity of Beatlemania one day gave way to sober secularism, and one day the same change will come for Taylormania, and God, if you think this book looks stupid now…

RELATED

Interestingly, I had written this down as a note while reading, and then about halfway through the book Nelson says “Dickinson—who is probably, along with Plath, the most famous of female-American poets (maybe of all American poets).”

Is that even really true of Plath?

Hannah Ewens wrote a piece about The Slicks that includes this same argument Nelson preempts, and, you know what? She’s right. You don’t even really need to say much more about it. And yet I will nevertheless say way too much more anyways.

The actual subject of Douthat’s piece was how Taylor’s new album was both conservative and crass, and how he feels about that as a notable conservative himself—I think he puts this tension rather interestingly, so I’m supplying it in an aside for interested readers:

The tension between feminist and Hefnerian visions of sexual liberation, for instance, was a lasting feature of social liberalism from the 1960s through the early 2000s, with each tendency remaining part of the same coalition because they were both arrayed against the old religious consensus. If progressivism made room for both Playboy and Ms. magazine for two generations, conservatism might make room for its traditionalists and its unwoke libertines for longer than you might expect.

Note again Nelson’s language here—while she classified those who think Taylor’s work references Plath as “many,” she classifies the critics of Taylor’s music from the angle of its commodification as merely “some.” Elsewhere she chastises “a few grumpy critics” (I suppose that includes me).

Becca Young, who I reference later, makes a similar connection, though one which has more to do with the potential for Nelson’s projection onto and identification with Swift, which I think is worth acknowledging as well:

The shadow of Nelson’s MacArthur Genius Grant, awarded for her work in memoir, hangs heavy over Nelson’s claims about the societal denigration of autobiographical art by women. There are a number of strange, almost meta moments in the text, where Nelson quotes Eileen Myles and Nietzsche to prove that art is inherently autobiographical, “the confession of its originator.” So, what is Nelson confessing with this book? She’s a Swiftie, no doubt, and a fan of Plath. She is upset that someone, somewhere, doesn’t like autobiographical writing. She is anxious about her own reception as a prolific woman author, but doesn’t feel justified in saying it outright?

At one point, Nelson says this:

The internal compulsion that drives some people to make art obviously differs from the external demand that we work for bread; that was Marx’s whole point, in distinguishing “the realm of freedom” from “the realm of necessity,” and aligning unalienated labor with the former, and exploitative work with the latter.

This is the sort of reading of Marx I might expect from a first-year college student who didn’t actually finish her assigned reading for the week rather than someone who allegedly teaches critical theory. No, that is not Marx’s “whole point”—the “realm of necessity” is not, in fact, “aligned” with exploitative work. Even after the abolition of capitalism, the realm of necessity remains, it is the necessary labour for survival. “Exploitation” is a social relationship between those who own the means of production and those who don’t, the point is to reorganize society so that necessary labour is collectively regulated, and ideally minimized so as to maximize the “realm of freedom.”

Nelson seems to think that it can be taken for granted that “Marxists” (a rather broad category) believe that a revolution will occur and then we’ll all have unlimited and frictionless freedom forever, which she pushes back against as being a foolish idealization. She’s right to, because it is a foolish idealization. But it’s also not what most serious “Marxists” believe. Firstly, “the revolution” as conceptualized within most forms of Marxism (including that of Marx himself) is a process of indefinite length (consider Marx’s famous conception of the “permanent revolution,” for instance). Secondly, the “freedom” Marxists are considering is the sort of freedom which matters, freedom from need.

Another point:

[T]his paradox will always be with us, doubling down on the familiar—often leftist—insistence that our salvation lies in liberating ourselves from the dark clutches of need and ascending to freedom’s bright expanse is not good enough, nor is simply exalting need, care, and obligation in freedom’s place. The former conjures an all-too-familiar schema in which self-sufficiency and independence are valued over reliance, service, and infirmity; the latter throws the door open to all kinds of unrealistic and dysfunctional demands made of ourselves and others, bringing us into mirthless territory ranging from codependency to shaming to servitude.

This feels too stupid to even comment on. “Liberating ourselves” along “leftist” lines does not necessitate “valuing” self-sufficiency and independence over “reliance, service, and infirmity”—those things are baked into the bread. It is a nonsensical claim requiring serious support in order to make it, support Nelson never provides.

I do not “care” for [har har] the empty and depoliticized “care ethics” that Nelson subscribes to, and, generally-speaking, Nelson’s considerations of freedom are bourgeois, liberal ethics, divorced from structural realities. It’s bogus.

i clung to every word. i am a longtime maggie nelson detractor and i feel so vindicated. i am not at all surprised that she wound up here. sorry you had to read that, but so glad you did, to take us on this ride. thank you!!!!

I haven't read the book so can't comment on its quality. But it seems, based on your review, that Nelson doesn't consider the fact that Plath's poetry is infused with a sense of doom. There are many references to suicide in her work. She wrote a novel that revolves around attempted suicide. I like Swift's country albums—shrug at her pop stuff— but there's no doom in any of her songs.