Why is the sky falling up?

And also something about the disappearance of literary criticism

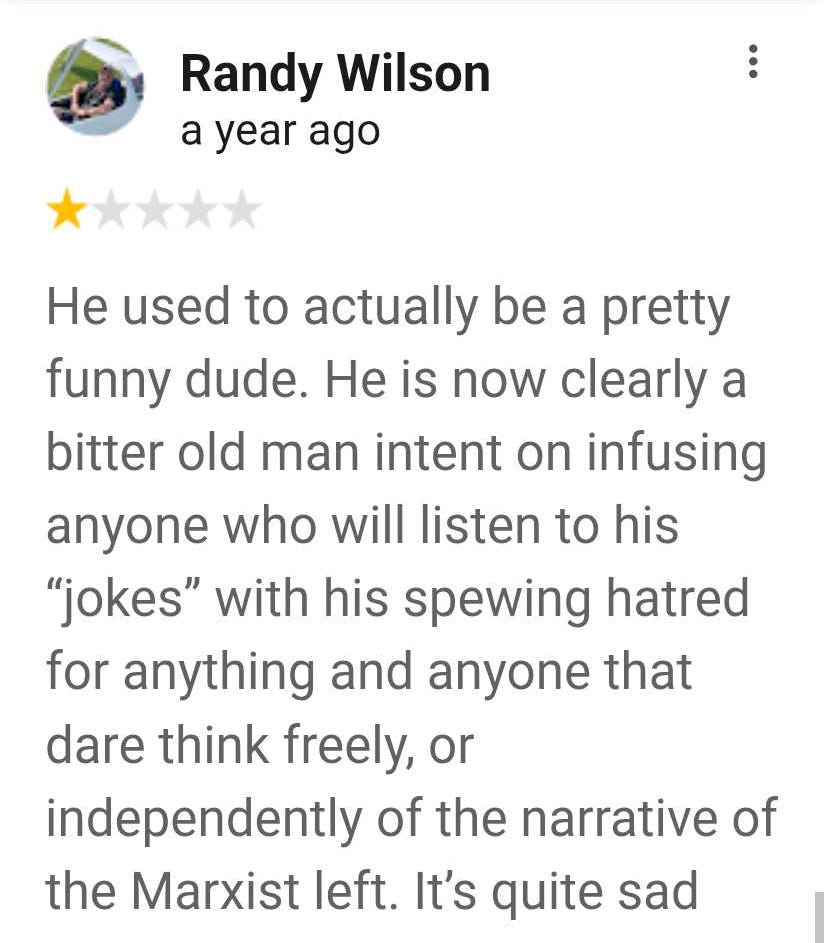

So, as I’m sure most of my readers already know, Colbert’s Late Show is getting cancelled. I don’t really give a shit about Colbert or his show, so that’s not going to be what this one is about,1 but here’s a Google review I stumbled onto by one Randy Wilson:

Randy clarifies that Colbert used to be funny. His satire used to seem reasonable. But something… something has changed. Lately it seems like all Colbert wants to do is work to uphold “the Marxist left.” I used to feel closer to this guy, Randy suggests, but suddenly he seems to be rapidly moving away from me, where is he going? The only other Google review Randy has up is one giving five-stars to the documentary The Principle, which claims that Copernicus was wrong and the Earth is the center of the universe. All around him, Randy sees the people he used to see eye-to-eye with receding into the horizon. Slowly they begin to disappear over its edge, an edge that simultaneously seems to grow smaller every day. “Where are they all going?” thinks Randy. “And why is the sky always falling up?”

I don’t think I need to explain to many of you that Stephen Colbert is not a “Marxist.” Colbert is a milquetoast liberal, the same kind he’s always been. I don’t know if his politics have really changed much in his thirty years on television. Has he ever come off as bitter, either under his old Colbert Report persona or now? If anything, I’d say I find Colbert more smarmy than anything, with a particular inane liberal smugness that has felt increasingly out-of-touch with the severity of the circumstances around him as time goes on. Colbert as a person never really changed, and part of his own downfall is owed to that—beyond the obvious political pressures, he was, at the end of the day, a man of a world that had long since crumbled beneath his feet while he remained floating in mid-air, like Wile E. Coyote past the edge of the cliff.

What Randy is unaware of is that if this figure he has been looking at has been completely unmoved for decades then it is, quite obviously, Randy who has been moving. I think this sort of unknowingly drifting umwelt is typical of a wide swath of the general Trump base. Unaware of how far they’ve slid, as far as they’re concerned it’s everyone else who has lost their minds. Not to say they also haven’t, I guess. Anyways, just some thoughts.

Okay well onto another topic: is lit crit going the way of the dinosaurs?

Have you heard I’m a ghost? Boo!

Adam Morgan recently suggested I might be vanishing—the Chicago Review of Books editor wrote a little piece bemoaning the slow (or perhaps fast?) disappearance of literary criticism. Oh dear. This does not bode well for me.

I saw a couple people online get mad at the piece for “self-indulgence,” but I think they sort of missed that the piece was clearly more of a personal essay about Morgan’s career history (supplemented with anecdotes from other critics) than a treatise on the place of literary criticism in the modern world. For that same reason, I’m not going to wring his neck too hard for any points I disagree with him on, because I don’t think it’d be entirely charitable to try to see his piece as primarily focused on an “argument” so much as it provides a frame for Morgan to reminisce on his career up to this point and opine on how things have changed around him—which is fine, I don’t see why anyone would take issue with that premise.

To start his piece off, Morgan makes the claim that literary criticism is equal in its merit to literature itself, and this is a line I’ve heard from a number of critics. It’s an understandably tempting one to endorse, but as a fellow pair of boots in the trench to Morgan I’ll respond as such: I enjoy being a critic even more than I enjoy being a poet, it provides me more fulfillment, but I ultimately feel my role as critic is subservient to literature. While I’m proud of what I do, I do it—even when I’m being a deliberate troll—to support the general project of literature, not to equal it. I love good criticism, but it is seldom something which for me reaches the transcendent capacity of good art. One of my all-time favourite literary reviews is Wendy Doniger’s “Hang Santa,” which on my first read brought me to tears. I still get goosebumps whenever I so much as think about its ending. But this is an uncommon occurrence. Literary criticism does not usually reach such places.

Or not for me, anyways. I strongly agree, at the very least, with Morgan’s concern about the reduction of criticism by means of purely instrumental logic to some sort of ephemeral or commercial pursuit. I just don’t think we have to overshoot our response to that and make it seem like we believe that, I dunno, James Wood is equal to Flaubert or something.

Is literary criticism really disappearing? It’s certainly changing. “When traffic is driven by search and social media, you will simply have more people click on a headline like ‘The 10 Best Haunted House Novels’ than a review of an individual haunted house novel that they likely haven’t heard of,” says Lincoln Michel in Morgan’s piece. This very much goes hand-in-hand with what I quoted Saul Austerlitz as saying about music criticism in my piece on Poptimism, how click culture and individual article metrics vs. whole magazine sales encouraged an article-to-article emphasis on engagement that has flattened subtlety and diversity of content somewhat (read: a lot). This is to say nothing of how much this was all encouraged by the financialization of the media as it, like everything else, was reduced to assets. Morgan is very accurate and succinct on this latter point:

…the real nail in the coffin was when private equity firms and hedge funds started buying newspapers and magazines and running them like Silicon Valley startups. (Between 2002 and 2019, the number of newspapers owned by private equity funds increased from 5 percent to 23 percent, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research.) When the vulture capitalists started slashing newsrooms to maximize shareholder value, they looked at all kinds of performance metrics. Guess which sections were the first to go?

Morgan is especially concerned in his piece about book reviewing, and… that may be under a significant threat, yes. Your average person reads, at best, four or five books a year, and it’s usually just some shit they just picked up at the airport or something their friend or a normie podcast recommended to them. Most of them aren’t even fiction. There was a period of about ten years where my mother didn’t read a single novel. And when people like my mother do, it doesn’t arrive in their hands by way of a critic’s word. To quote Austerlitz again from his piece I referenced before: “most people prefer their iPods or Spotify playlists or Pandora stations to fusty radio programming.” The same is true of books; when they are even being read at all, it’s not usually at the recommendation of people like Morgan or myself. This of course all ties into the waning of critical authority, which is tied to a social development I harp on all the time, which is the general attitude we’ve come to accept as “aesthetic nihilism”: nothing can be called “good” or “bad” anymore because “that’s just your opinion, maaaan,” and while that “let people enjoy things” mentality may seem to be a little Zen at first, it is in fact soul-destroying. You can read more of our collective’s thoughts on that in our Heel Manifesto:

Your Poetry Sucks: The Heel Manifesto

We are living in an era of aesthetic nihilism. Nothing is true, so everything is permitted. But if nothing means anything—if nothing has any relative “value” next to anything else—then why try? After all, it’s just as valid as anything else. Don’t you WANT to live for more than that? Don’t you WANT to see your work as the expression of something worth taking preciously?

But all is not lost! Probably. Maybe. Sort of. More people I know seem to be reading literary criticism than ever, mostly thanks to websites like this one. I know you know it exists, Adam! Because I just tagged you! This is perhaps another prong of what is killing traditional literary criticism as we knew it in the previous century, the decentralization of opinion and its diffusion into these open-season platforms, or even—and Adam, my man, I’m sure you and I are condemned alike to groan at this one—BookTok.

There is another aspect of all of this I want to talk about. (“IT’S A GOD DAMN THREE PRONGED ATTACK???” you scream, shocked, at your device. And, I mean, kind of.) One of the reasons for the death of paid lit crit gigs is right under Morgan’s own nose. While he addresses the real problems of low compensation and precarious working arrangements, he doesn’t address the structural logic of creative labour within the culture industry deeply enough for my taste, or the role of literary institutions (publishers, MFA programs, etc.) in reproducing these conditions. He tells an anecdote about being picked up by Jessa Crispin to write for Bookslut, but jokingly points out how it wasn’t paid. But that was when he was a mere unproven amateur. Years later, he was (rightly) offended when he was offered a role running the Chicago Sun-Times book pages for free. He said no.

Morgan only passingly mentions that he has an MFA. The MFA is itself is a vital ingredient in the poison in the well, as it functions within cultural production as a form of professional degree that, among other things, encourages unpaid creative labour. It, by its nature, formalizes creativity into employability, and turns writers into a managed and stratified workforce. They are indoctrinated not only into modes of style but also exit the university ready-made for institutions that can’t or won’t pay them. They are told and see through example that this is a mandatory part of “the career” and may even be made to do such unpaid labour while within the program as well. In this way, the MFA is both gatekeeper and holding pen. These forms of labour are naturalized, and the expansion of the MFA programs has (intentionally) produced a glut in the creative workforce which leads to analogues to unpaid internships and precarious gig-work. Material capital is traded out for cultural capital. That is the lot of the creative worker.2

More optimistically: certain gates which were once closed are now open. It’s unlikely that I, without an MFA under my belt, would get far in professional literary criticism. However, I now have a platform where tens of thousands of people a month come and read the things I have to say about books. And then tell me to kill myself. Mind you, not many of those people pay me for the privilege of telling me to kill myself, because I’m just giving it away for free like the little slut I am.

Morgan gives us a bit of a sappy ending in his piece:

“What’s the difference between a well-written review and a fantastic review?” I ask Alexandra Jacobs.

“Courage,” she says.

While that may be posed a little sentimentally, Jacobs isn’t wrong, and Morgan isn’t wrong for focusing on this verbiage. They’re right. It does take courage, and far more critics ought to remember that.

That’s me doubling down and doing the sentimental thing I was just complaining about too. You know, like a goof. And now I’m undercutting it like some cringe Joss Whedon MCU character or something. Anyways, have a good one everybody!

Yes, the show’s cancellation is probably at least somewhat due to CBS’s takeover by Trump surrogate Larry Ellison and the increasing media censorship that comes with it, although it should also be noted that 1) Colbert’s show was indeed not doing too hot in the first place, and 2) CBS more than any other network was already under near-direct CIA control for decades, so it’s hard to say its “independence” is being threatened considering it never really had any.

I wrote this a week ago and slid it into the queue, but unfortunately was just shy of yet another brouhaha concerning compensation in creative industry labour, the concern over whether or not n+1 offering $60k as a salary for an entry-level position is “exploitative” or not. Luke McGowan-Arnold put it aptly: “proves again that almost no one with ‘leftist politics’ hangs out with poor people cause 60k isn’t a ton of money but there’s a lot of people in the United States who live on less than 25k a year.” Like, I would kill for that kind of money for a magazine job (Ross Barkan also pointed out that, I mean, n+1 is a non-profit). Focusing on n+1 obscures why such pay is actually of course very good for a magazine job, which I outlined above—very few of n+1’s critics would want to admit to my points of course because they are mostly bougie MFA-holders themselves who often already possess the material background necessary to be able to afford to do a helluva lot of unpaid labour while they coast off of daddy money.

the problem is everyone is a griswold and no one wants to be an edgar a. poe ): and now everything is compilation of poems and critiques that people paid to have be there. its like giswold murdered poe in more ways than one...

Excellent, thank you